Rudyard Kipling's home - A Passage to India amidst the English Countryside

In my ongoing wanderings around England, I couldn’t resist visiting the place that was home for more than 30 years to Rudyard Kipling, the author of one of my favourite childhood tales, The Jungle Book, made even more popular in the animated version of the Disney film adaptation appeared in 1967 which I believe I have watched more than 50 times in different periods of my life: first as a child, later as an adult with my children, loving it equally in both occasions.

Just a 15 minute drive from where I live, in the village of Burwash in East Sussex, Bateman’s is a Jacobean Manor built in local sandstone dating back to 1634 as the inscription over the porch reads, where Kipling lived from 1902 till his death in 1936, rejoicing his seclusion in this tucked away estate in the Sussex Down, set at the bottom of “an enlarged rabbit-hole of a lane” as he describes it, where he could find the calm and tranquillity he needed to write for he was at the time probably one of England’s most famous writers. Just a few years later, he was to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature, striking two records, being the first English writer to be awarded the prize and the youngest in history.

Kipling loved the place. It was what he needed to go through the grief for the loss of his beloved daughter, who had died of pneumonia just a few years earlier aged six, a loss from which he apparently never recovered completely. In Something of Myself he describes the emotions that the house immediately aroused when they first saw it:

“We had seen an advertisement of her, and we reached her down an enlarged rabbit-hole of a lane. At very first sight the Committee of Ways and Means [Mrs Kipling and himself] said 'That's her! The only She! Make an honest woman of her - quick!'. We entered and felt her Spirit - her Feng Shui - to be good. We went through every room and found no shadow of ancient regrets, stifled miseries, nor any menace though the 'new' end of her was three hundred years old...”

I love how Kipling refers to the house as a “she” and not as an “it” gifting the place with a soul and personality. He apparently had very strong feelings about his homes as he had even named his first house as a married man, Naulakha, priceless jewelin Hindi, the house where he first lived with his American wife just after their wedding, a place in the nature in Dummerston, Vermont, now owned by Landmark Trust USA that maintains it as a vacation rental. Quite an interesting retreat for someone wanting to finish a book or finding some inspiration working in Kipling’s study. Maybe at a certain point I might consider it myself! It certainly provided plenty of seclusion and inspiration to him since here it’s where he wrote most of his most famous works from The Jungle Book (1894), The Naulahka: A Story of West and East (1892) and The Second Jungle Book (1895), Captains Courageous, The Seven Seas, and much of The Day's Work and Many Inventions among others.

It’s fascinating to imagine how Kipling looking out from his studio’s window to the snowy landscapes, dreamt of his native India and wrote about a land he knew well from his childhood and early years of work as a journalist in Bombay and a tropical jungle he had actually never visited, the Seoni jungle, in the central state of Madya Pradesh, drawing his inspiration instead, according to his many biographers, from the recollections and the photographs of his friends Aleck and Edmonia and publications like, Robert Armitage Sterndale’s Mammalia of Indiaand Sterndale’s 1877 book Seonee: Or, Camp Life on the Satpura Range. Probably he was also inspired by his father’s illustrations in Beast and Man in India: A Popular Sketch of Indian Animals in Their Relations with the People, which was published in 1891. His father, an artist, illustrator, museum curator and art teacher will also provide images for The Jungle Book and Kim.

Kipling travelled in real life as much as he did in his imagination. India was exotic and wondrous and the memories of his childhood strolls with his nanny in the crowded Indian markets, the cosmopolitan mass you would come across in the busy streets: Anglos, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists and Jewsand the colourful bedtime stories recited in a language he learnt even before English were vivid in his memory. He later spent most of his childhood, from the age of five till the age of sixteen, in England, where he was educated, but as soon as he was given the possibility he made his way back to India. He started travelling even more after he got married, starting off with an adventurous and unusual honeymoon to Canada and Japan, followed by the couple settling down in the States for several years and then relocating back to England. He continued to travel extensively and regularly visited South Africa where he would spend the winter months till late in his life.

He knew what relocation and living abroad as a foreigner was all about and that’s why I think home, a safe nest where to get back to, was even more important to him than it might be for others. Migrating birds need a safe landing place to rest in between one voyage and another and Kipling found his first one in Vermont and later on another at Bateman’s.

"Behold us," he wrote in a November 1902 letter, "lawful owners of a grey stone, lichened house—A.D. 1634 over the door—beamed, paneled, with old oak staircase and all untouched and unfaked."

Talking about his time in Vermont, Kipling wrote:

“Better than all, I had known a corner of the United States as a householder, which is the only way of getting at a country. Tourists may carry away impressions, but it is the seasonal detail of small things and doings (such as putting up fly-screens and stove-pipes, buying yeast-cakes and being lectured by your neighbours) that bite in the lines of mental pictures.”

And this is an aspect of Kipling’s writing that got me more and more interested in his work as an adult, because Kipling addressed, among the first, all that’s related to cultural exchange, cross cultural encounters and those feelings that haunt anyone who has lived elsewhere than their place of birth: the familiarity you feel for the new place and its incongruity, the feeling of belonging combined with the one of extraneity, the duality of balancing between cultures that are absorbed maybe at different levels but are still part of your identity nevertheless and often conflict, confuse you and keep you constantly longing for the “other” place. But more on this later. Let’s go back to Bateman’s.

At Bateman’s Kipling continued writing, however he never got back to the children stories he had enjoyed so much writing for his daughter in the past, like 'Stalky and Co.' (1899), 'Kim' (1901), etc. Even the Jungle Book had been written for Josephine and the last book that he wrote for her was 'Just So Stories' that was published in 1902, named after what Josephine used to say when she would ask her father to repeat each tale as he always had, or "just so,”. Just So Storieswere greeted with wide acclaim. Kipling's books during his years at Bateman's includes Traffics and Discoveries (1904),Puck of Pook's Hill (1906), - the hill can be seen from the lawn at Bateman's, to the south-west - Actions and Reactions (1909), Rewards and Fairies (1910), Debts and Credits (1926), Thy Servant a Dog (1930) and Limits and Renewals (1932).

Walking through the house is a surreal experience. You get the feeling the people who live there have just gone out running some errands and will soon be back.

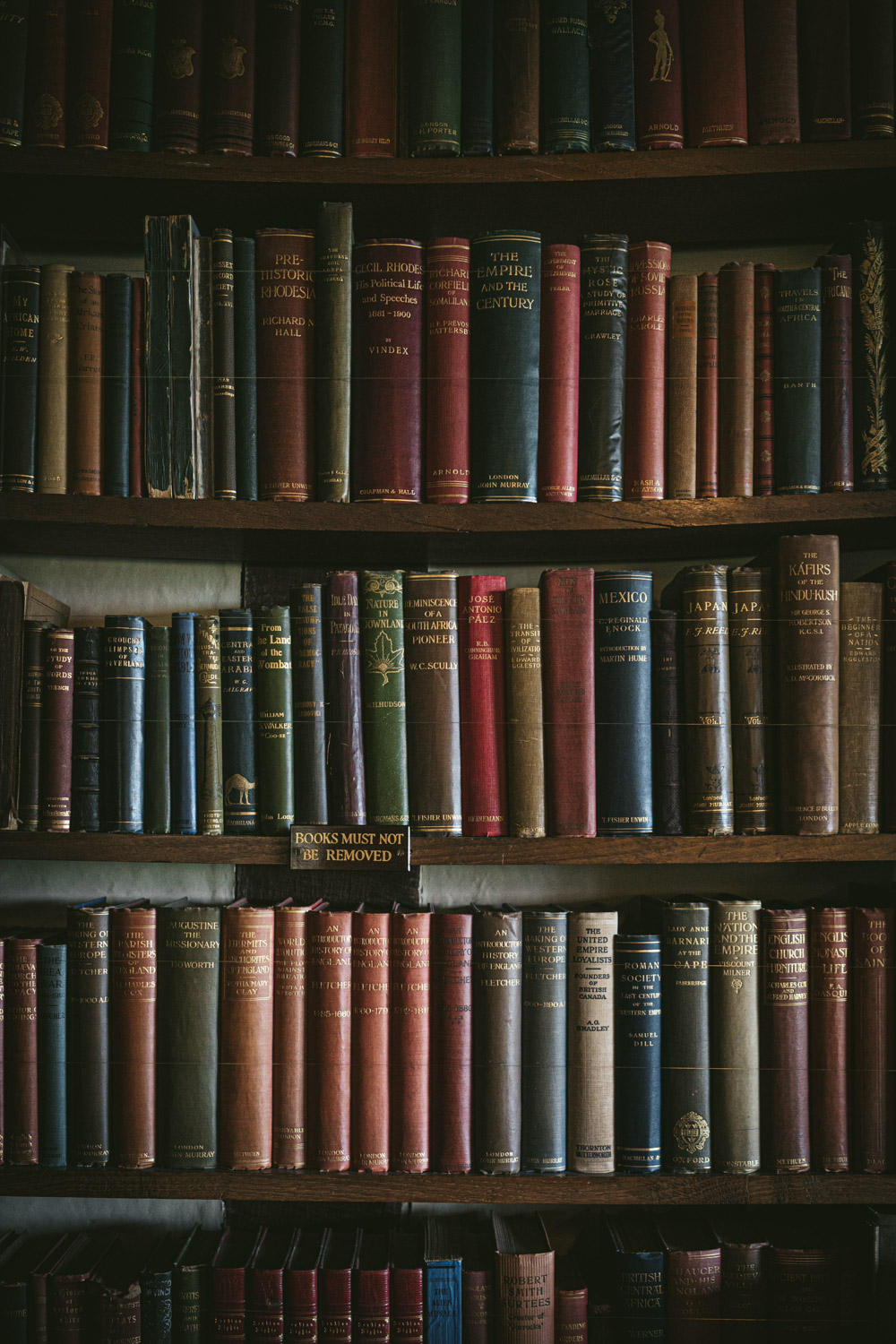

A collection of memorabilia from Kipling extensive travels is in display and India is well represented in every room. You can go through many handwritten notes now collected in albums that you are free to peruse while sitting in the little dining room with the tiny 1930s radio and the comfy armchair near the window. The house has in display the Nobel Prize for literature, the paintings from the Jungle Book and Kipling’s 1928 Phantom 1 Rolls-Royce, but it’s in his studio I lost myself for more than an hour, studying the shelves of the extensive library where countless volumes on India and other countries and cultures of the world are neatly piled, next to atlases and dictionaries and the works of authors like R. L. Stevenson and geographers of his time. The two globes, the desk with writing paper scattered, the author’s spectacles and exotic paper holders are among the numerous objects you can study in this room of marvels that is the most fascinating space of the house for all I am concerned.

Many says Kipling lived here in seclusion but we can find many visitors in the guestbook with some well-known personalities in the like of Henry James, H Rider Haggard, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Cecil Rhodes, Max Aitken and King George V. In the same room we can admire some early editions of his work, however most first editions and the notes and drafts known as “the file” are now in the British Library, donated by his widow in 1939 when she died. At the time of her death she also bequeathed Bateman’s Manor to the National Trust, as a memorial to him, for all to enjoy forever.

In every room you will find a National Trust member ready to give you as much information on the house and the specific room as you like. I had a lengthy chat with the gentleman in Kipling’s office discussing the slightly more controversial aspects of Kipling life and the way posterity has read his work and I am happy to say he corroborated my opinions on some historical misreading of the author’s literary production.

Kipling has known a period of unpopularity after the First World War due to his alleged colonial supremacist views that many felt was embedded in his narrative and poetry. This perception of Kipling has fortunately greatly improved, but and some these views survive till today. The truth is, Kipling was a man of his time but his views where much more complex and articulate that many wished to admit.

Personally, I think he deeply explored the notion of being a westerner in other lands and him being a colonialist at the time when he lived in India simply amplified experiences, contradictions and cultural exchange issues that are still pretty similar in our today’s non-colonial world for those who live as westerners in countries that have a very different cultural background, regardless of the fact that we speak of India, Africa or elsewhere. His work is actually showing a very deep understanding of the many contradictions that distinguish these type of cultural exchanges that go well beyond the superficial approach of many well-wishing westerners of our time. Something that the committee who decided to award him the Nobel Prize seems to have grasped since the awarding message praised the fact that he “brought India nearer to home than the opening of the Suez Canal”. Kipling, it said, did more than any other “to draw tighter the bonds of union between England and her colonies.”

His relationship with India is rooted in profound love. Kipling so describes India through the voice of Kim: “A fair land — a most beautiful land is this of Hind — and the land of the Five Rivers is fairer than all…” and today scholars have finally taken a less emotive approach and Kipling is now recognised as one of the most authentic voices of the life and character of the British Empire, Empire being an historical fact and not a political view.

Kipling wrote to Margaret Burne-Jones : “When you write ‘native,’ who do you mean? The Mahommedan who hates the Hindu; the Hindu who hates the Mahommedan; the Sikh who loathes both; or the semi-anglicised product of our Indian colleges who is hated and despised by Sikh, Hindu and Mahommedan...”. I challenge any expat who has lived in a non-western country to admit he has not been reflecting on stereotypes such as ‘native’ and “non-native” and to admit he has not been undergoing reflections on cultural differences and what means being us or they, what is the impact of our presence in their land, etc…

In a poem by Kipling:

WE AND THEY

All good people agree,

And all good people say,

All nice people, like Us, are We

And every one else is They:

But if you cross over the sea,

Instead of over the way,

You may end by (think of it!) looking on We

As only a sort of They!'

Kipling was born in India and was raised mainly by Indian servants, to the degree that he had to be reminded to speak English when in the presence of his parents. His work has the evocative power it has because he decided to use many fragments of the Indian language, simply because as any expats know, he couldn’t have done otherwise. Certain things must be expressed necessarily in one language, or they will lose their flavour and their meaning will be washed out and allowed to faint away.

He drew his universe of flavours, smells, noises and sounds not only from the recollections of the time spent with his Indian ayah, the word for nanny that is still used even in Kenya, but also from his young years in Bombay and Lahore where he used to visit opium dens, bazaars and gambling houses, absorbing the chaotic life of the city. India was intense and captivating. In his words "the heat and smells of oil and spices and puffs of temple incense, and sweat, and darkness, and dirt and lust and cruelty, and, above all, things wonderful and fascinating innumerable." Nowhere in his writing we perceive he wishes of seeing India or south Africa, where he will spend long periods later, or anywhere else changing their traditions, religions, and culture. He obviously had his own culture, as any of us, and might have not fully understood or subscribed all that the foreign ones entailed, but that didn’t mean he ever advocated for a conversion or transformation of those lands and their people. In his words again: Indians "should be allowed to enjoy the practical benefits of the Raj peace and justice, quinine and canals, railways and vaccinations without having to submit to Western notions on education and religion."

This aspect makes his writing all the more interesting to me and I believe it can give a much deeper insight into what being a traveller, an expat or a full time settler in other countries means. It also brings to light what being curious, respectful and understanding of traditions and customs it’s all about, in a much more meaningful way than the sugar-coated propaganda I often hear in westerner’s rhetoric speeches about these topics, with their banned words, because they might conjure monsters of the past we want to forget have even existed, and their forced appreciation, turned into a dogma you must abide to in order to be considered non-racist.

So, I encourage you to go back to reading the works of Kipling with an open mind and an open heart and to visit and honour his ashes that are buried in Westminster Abbey in Poets' Corner next to the graves of Thomas Hardy and Charles Dickens with no fear or shame to be learning from a man who wasn’t perfect, who lived his life in his times, not ours, and has known cultural diversity from within.

https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/batemans

https://landmarktrustusa.org/properties/rudyard-kiplings-naulakha/